Some while ago, preparing a piece for the British Ecological Society’s Bulletin on the general scarcity of female ecology professors, we had the pleasure of interviewing Professor Anne Glover. (Shortly afterwards Anne went on to become EU Chief Scientist. Coincidence? You decide…) One of the things that Anne talked to us about was the importance of informal social networks in career progression within science. Business conducted after hours, over drinks. Basically Bigwig A asking Bigwig B if he (inevitably) could think of anyone suitable for this new high level committee, or that new editorial board; Bigwig B responding that he knew just the chap. That kind of thing. In some ways this is one of the less tractable parts of the whole gender in science thing. Much harder to confront, in many ways, than the outright and unashamed misogyny of the likes of Tim Hunt, simply because it is so much harder to pin down. We know that all male panels in conferences, for instance, are rarely the result of conscious discrimination, more often stemming from thoughtlessness, laziness, or more implicit bias.

With something as public as a conference, of course, then we can easily point out such imbalances, and smart conference organisers can take steps to avoid them. (My strategy, by the way, is to identify the top names in your field, and invite members of their research groups. Has worked wonders for workshops I have run.) But how to get more diversity out of those those agreements made over a pint (or post-pint, at the urinals)?

One way is to take steps to help a wide range of early career scientists to raise their profile. Be nice to them online, invite them to give talks, promote their papers, and so on. But another way into prominence is through publishing. Not your own papers (though that helps, of course); but the process of publishing others. Get a reputation for reviewing manuscripts well, and invitations onto editorial boards will follow. From their, editorial board meetings and socials, and your name starts to gain currency among influential people.

All of which is fine, but peer review is an invitation-only club. If you’re not invited, you’re not coming in.

Which brings me to the point of this post. I’m on a couple of editorial boards - Journal of Animal Ecology and Biology Letters. As a handling editor, I am responsible, among other things, for inviting referees to review manuscripts. And when I do this, you can bet your life that I will be calling on those potential reviewers nominated by the authors. Not exclusively, but certainly they will figure.

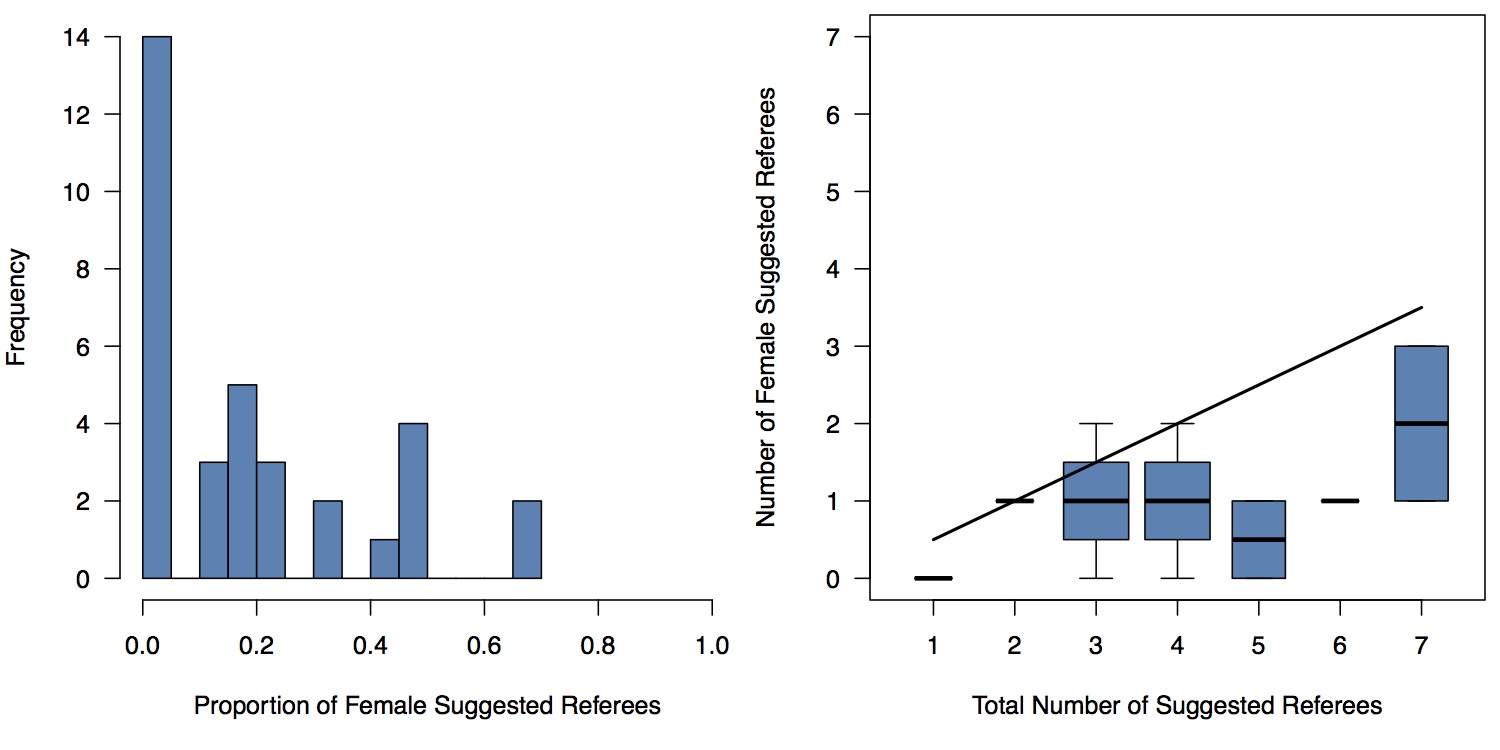

And I started to wonder what kind of gender balance there might be among these suggestions. 34 papers in, here’s your answer. (I should stress that the identity of the journals has no bearing on the following, all statistics are purely the result of choices made by submitting authors.) Over 40% of submitting authors did not suggest any female referees, with female suggested referees exceeding males on only 2 occasions, and a median proportion of 15% female suggestions. The number of suggested female referees does not increase with the total number of referees suggested, neither is there any relationship between the proportion of female authors (median in this sample of 1/3) and proportion of female suggested referees (correlation of 0.05, if you want numbers). Here’s a couple of figures:

What’s the message here? Maybe we need to start thinking more carefully about lists of names we come up with, not just when these choices will be public - speakers at a conference for example; but also - perhaps especially - when they will not. And not just because of benefits that reviewers may or may not eventually receive in terms of board membership and so on. We get quickly jaded about the whole process of reviewing manuscripts, and forget too soon what a confidence boost it can be to be asked.

And just a coda: I’ve been thinking about this blog post for some time, a year at least. What is depressing is the number of occasions over that year - Hunt’s ridiculous outburst merely the most recent - when I have thought ‘I must get that post written, it’s so topical right now.’ How many years since Anne Glover outlined all these issues to us? (Eight, and counting.) How much has actually changed?

Well, one thing has, at least - the rise of new social networks, the online community that can be cruel but can also be incredibly supportive, providing a voice for those whom certain public figures would prefer to remain mute. These networks are open, no longer dependent - thank goodness - on 1950s values, beer-fuelled patronage, and old school ties.