The editor of a well-respected ecological journal told me recently, “I am… very down on analyses that use citation or bibliographic databases as sources of data; I'm actually quite concerned that the statistical rigor most people learn in the context of analysing biological data is thrown out completely in an attempt to show usage of a particular term has been increasing in the literature!” I think he has a point, and in fact I feel the same about much that I read on bibliometrics more generally: there’s some really insightful, thoughtful and well-reasoned text, but as soon as people attempt to bring some data to the party all usual standards of analytical excellence go out the window. I see absolutely no reason to buck that trend here.

So…

The old chestnut of Journal Impact Factors has been doing the rounds again, thanks mainly to a nice post from Stephen Curry which has elicited a load of responses in the comments and on Twitter. To simplify massively: everyone agrees that IFs are a terrible way to assess individual papers (and by inference, researchers), but there’s less agreement on whether they tell you anything useful when comparing journals within a field. Go read Stephen’s post if you want the full debate.

But what’s sparked my post was a response from Peter Coles (@telescoper), called The Impact X-Factor, which proposed an idea I’d had a while back about judging papers against the IF of the journal in which they’re published. Are your papers holding up or weighing down your favourite journal? Let’s be clear from the outset: I don’t think this tells us anything especially interesting, but that needn’t put us off. So I have bitten the bullet, and present to you here my own personal impact factor. (The fact I come out of it OK in no way influenced my decision to go public.)

The IF of a journal, remember, is simply the mean number of citations to papers published in that journal over a two-year period (various fudgings and complications make it rather more opaque than that, but that’s it in essence). So for each of my papers (fortunately there aren’t too many) I’ve simply obtained (from my google scholar page, as it’s more open that ISI) the number of citations they accrued in the two years after publication. I’ve then compared this to the relevant journal IF for that period, or as close as I could get. Here are the results:

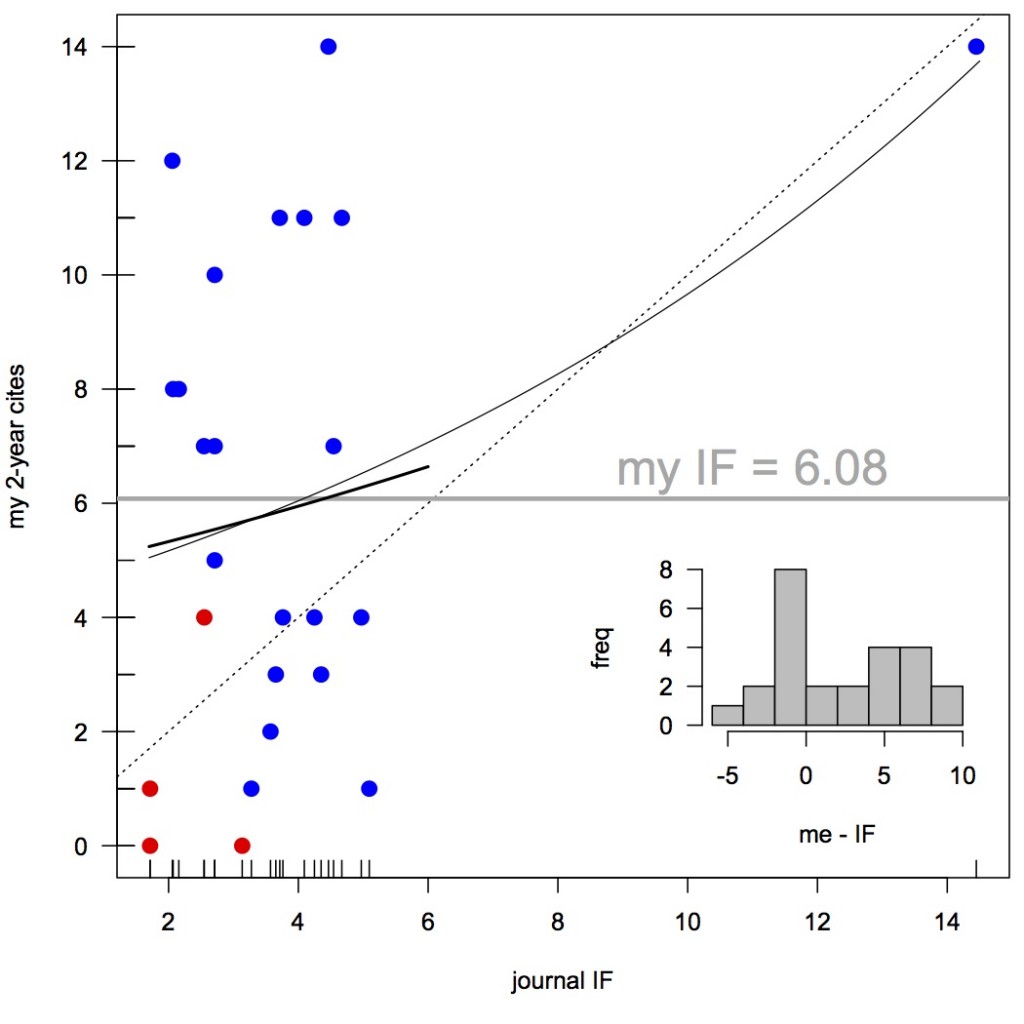

OK, bit of explanation. This simply plots the number of citations my papers got in the two years post-publication, against the relevant IF of the journal in which they were published. (The red points are papers published in the last year or so, and I’ve down-weighted IF to take account of this; I’ve excluded a couple of very recently-published papers.) The dashed line is the 1:1 line, so if my papers exactly matched the journal mean they would all fall on this line. Anything above the line is good for me, anything below it bad – the histogram in the bottom right shows the distribution of differences of my papers from this line.

I’ve fitted a simple Poisson model to the points, with and without the outlier in the top right – neither does an especially good job of explaining citations to my work, so we might as well take a mean, giving me my own personal IF of around 6.

As my editor friend suggested, there’s a whole lot wrong with this analysis. For instance, I haven’t taken account of year of publication, or any other potential contributing factors (coauthors, publicity, etc. etc.). Another obvious caveat is the lack of papers in journals with IF > 10 (I can assure you that this has not been a deliberate strategy). But back in the peloton of points which represent the ecology journals in which I’ve published most regularly, I’m reasonably confident in stating that citations to my work are unrelated to journal IF. Gratifyingly too, the papers that I rate as my best typically fall above the 1:1 line.

So there we have it. My own personal impact factor.